Details

Details

Just recently, the Danish consumer ombudsman announced that it had reported a Danish communications agency to the police. Why? The communications agency, according to the consumer ombudsman, had a misleading advert in two magazines it had issued. The ombudsman explained:

As a consumer, when you look at an advert, you need to be 100 percent aware that this is an advert. In this case it turned out that what the consumer was the led to believe was an editorial was, in fact, an advert.

The advert sported a headline, subheading, byline and pictures. There was no indication that it was an advertisement. A piece of advertising dressed as journalism and no way of knowing from a consumer's standpoint.

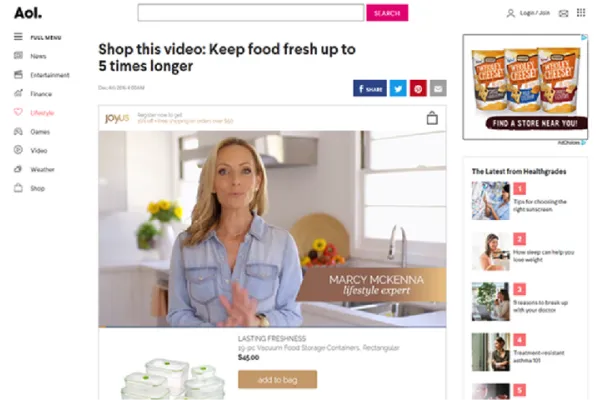

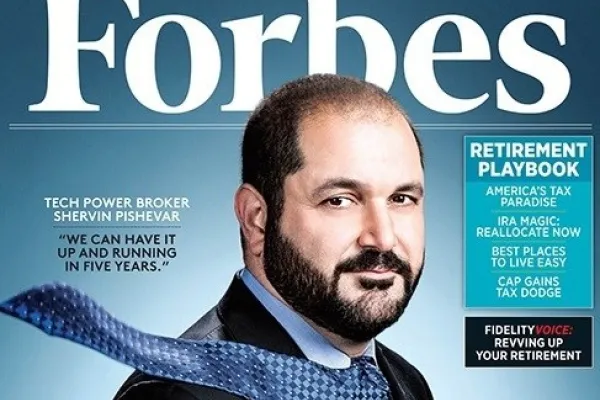

Critics of native advertising will point to this example, and similar cases of trickery, when declaring sponsored content or branded journalism the end of media outlets as we know them. What happened to the time when newspapers and magazines were trusted institutions that provided impartial and critical coverage of society's important issues and power brokers? It's over, the critics will say, and they will point to the cover of Forbes, which in March carried a piece of advertising that was barely identifiable.

Can't find it? Don't fret, because how were you supposed to know that FIDELITYVOICE: REVVING UP YOUR RETIREMENT is in fact sponsored content on behalf of Fidelity Investments? Sure, now that you know, it seems rather obvious. Why would Forbes name an item FIDELITYVOICE if it wasn't sponsored content on behalf of Fidelity? It probably wouldn't but consumers can't be expected to make those kinds of assumptions. And they shouldn't.

Forbes was criticized for its decision to place a hidden advert on the cover. And so, the entire reputation of native advertising took a hit. Consumerist.com wrote scathingly:

If you thought the demon who goes by many names — native advertising, advertorials, sponsored stories, promoted content, utter bullsh*t — was something that was relegated to the Internet, then go check out the new issue of Forbes, which not only comes complete with some of this bought-and-paid-for crap, but which actually lists it on the front cover of the magazine like it’s just another story.

There is no reason to make this overly complicated: If media outlets want to do native advertising without losing credibility, they have got to be up front and honest about it. Labelling is absolutely vital and we're not talking "labelling" by one's own self-serving, arbitrary standards (like when Forbes Media's Chief Revenue Officer, Mark Howard, defends the cover advert by insisting "When you look at the colour scheme and the box, it's separated, it has a different background"). Good labelling is LABELLING. It's clear usage of "SPONSORED BY", "PRESENTED BY", "PAID FOR AND POSTED BY" or some other intelligible variation of that simple message that the following content is financed by an advertiser and not to be confused with the standard editorial content. Bad labelling is "labelling". It's empty talk about colour schemes and background shades and it's suspiciously vague. We can all tell the difference. Every media outlet that decides to "label" is going to get scrutinised and rightly so.

LABELLING is not difficult. It is, in fact, immensely achievable both from a graphical, textual and visual standpoint. There are no excuses. And thankfully, most media outlets get it. Searching the internet and looking for native advertising, it is much more difficult to find examples of sponsored content that isn't properly labelled than the opposite (kind of self-evident, we know...but take a look at some of the biggest journalism websites that work with native advertising and they all label thoroughly).

The Huffington Post

The Guardian

BuzzFeed

Three pieces of native advertising that include clear labelling. Labels are placed in the exact area where you'd expect to find the staff writer's name. This is genuinely excellent and logical positioning if you want to inform the reader that something is different about content, right?

Is it perfect? Probably not. Some readers won't notice the difference, and they have, in a sense, been tricked. But employing the byline to convey a sponsorship gives the reader a fair chance to identify the partnership between publisher and brand.

Earlier this year, Civicscience released a study that revealed the crux native advertising finds itself in. 47 percent of respondents consider advertising the best way to fund objective journalism (public financing, charitable donations and paid access to content were in a distant second, third and fourth place with respectively 20, 18 and 15 percent.). However, 61 percent. of respondents think that sponsored content hurts the credibility of media outlets.

Another study, conducted by Adyoulike in the spring of 2015, found that 57 percent of UK internet users under the age of 34 will visit online content that appeals to them even if that content has been obviously paid for or sponsored. In conclusion: users don't mind sponsored content, but they won't tolerate shady advertising.

Media outlets with limited amounts of credibility are no good. Not from a consumer's standpoint, nor from an advertiser's standpoint. Native advertising needs to evolve to a stage where it's not in conflict with credibility. LABELLING is a good start.